Freediving Physiology: What Happens to Your Body Underwater

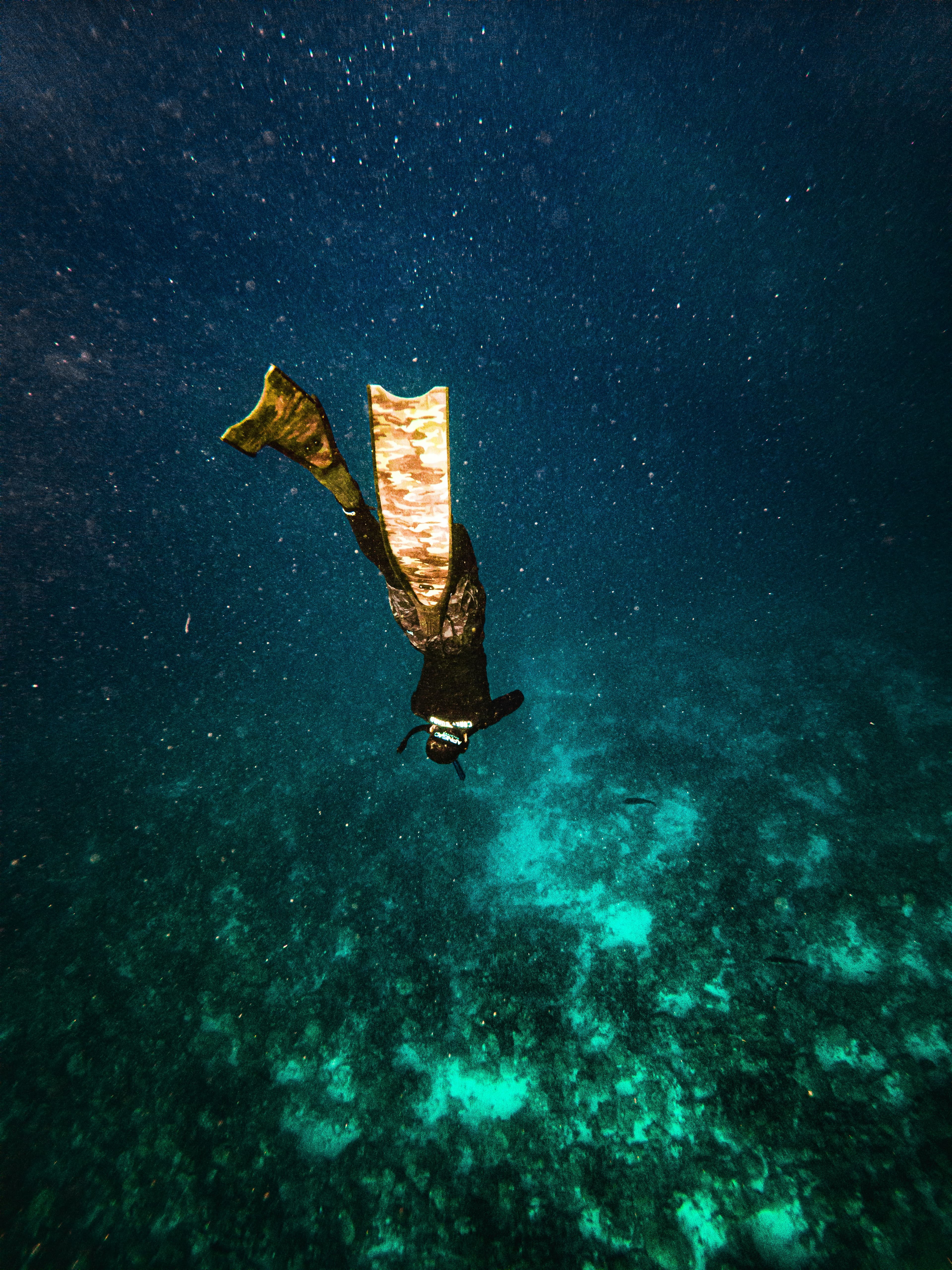

The moment your face touches water and you take that final breath, something extraordinary begins. Your body activates an ancient survival system—one shared with dolphins, seals, and whales—that transforms human physiology in ways scientists once believed impossible. Understanding what happens to your body underwater isn't just fascinating—it's essential knowledge for anyone venturing beneath the surface on a single breath.

For decades, scientists predicted that diving beyond 30 metres would crush human lungs. Then freedivers shattered those predictions, forcing researchers to reconsider everything they thought they knew. Today, elite freedivers routinely descend past 100 metres, their bodies executing a symphony of physiological responses. If you're new to the sport, our complete beginner's guide covers the fundamentals.

The Mammalian Dive Reflex: Your Inner Dolphin

The cornerstone of freediving physiology is the mammalian dive reflex—a powerful suite of automatic responses triggered the instant cold water contacts your face while you hold your breath. This isn't something you need to learn; it's hardwired into your nervous system from birth, though it can be strengthened significantly through training. For a deep dive into this fascinating reflex, see our complete guide to the mammalian dive reflex.

When receptors in your facial skin detect cold water during breath-holding, they send signals to your brainstem, which orchestrates a cascade of responses through both sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system activation. This is closely related to vagus nerve stimulation, which many freedivers deliberately train to enhance their diving response.

Bradycardia: When Your Heart Slows Down

The most immediately measurable effect is bradycardia—a slowing of heart rate. In untrained individuals, heart rate typically drops 10-25% upon face immersion. However, trained freedivers can experience far more dramatic reductions, with some elite athletes recording heart rates below 30 beats per minute during deep dives.

This cardiac slowdown isn't a sign of distress—it's an elegant oxygen conservation mechanism. A slower heartbeat means the heart muscle itself consumes less oxygen, leaving more available for your brain and vital organs.

Peripheral Vasoconstriction: Redirecting Your Blood

While your heart slows, blood vessels in your extremities constrict significantly, reducing blood flow to "non-essential" areas. This creates "blood shift toward the core"—more oxygenated blood remains available for your heart, lungs, and brain.

One side effect is lactic acid buildup in peripheral muscles. With reduced blood flow, muscles rely more on anaerobic respiration, producing the familiar "burn" freedivers feel during longer breath-holds.

Blood Shift: Protecting Your Lungs at Depth

Perhaps the most remarkable adaptation is the blood shift—massive redistribution of blood into the thoracic cavity that protects your lungs from compression. To understand why this matters, consider Boyle's Law: as pressure increases with depth, gas volumes compress. At 10 metres, your lungs compress to half their surface volume.

Research shows that over one litre of blood can shift into the thorax at 30 metres depth, filling capillaries around the alveoli and taking up space that would otherwise require air. This explains how divers reach depths that should be "physiologically impossible." Learn more in our comprehensive blood shift guide.

The Spleen Effect: Your Hidden Oxygen Reserve

Your spleen acts as a reservoir for red blood cells. During freediving, it contracts to release stored cells into circulation—a temporary "natural blood doping" effect. Research on the Sama-Bajau people of Southeast Asia shows they've developed genetically enlarged spleens from generations of breath-hold diving.

Gas Exchange and Blood Chemistry

Understanding oxygen and carbon dioxide dynamics during breath-holds is crucial for both performance and safety—and directly related to most freediving accidents. For a complete understanding of these critical processes, see our guide to O₂ and CO₂ dynamics.

The Oxygen-Carbon Dioxide Balance

When you hold your breath, oxygen is consumed while carbon dioxide accumulates. The urge to breathe is primarily driven by rising CO2, not falling oxygen. Your body has sensitive chemoreceptors that detect even small CO2 changes, creating increasingly urgent breathing sensations.

Oxygen levels, by contrast, don't create strong warning signs until dangerously low—which is why proper breathing techniques are essential. Training increases CO2 tolerance but doesn't change oxygen requirements.

The Danger of Hyperventilation

Hyperventilation before diving is extremely dangerous. Taking rapid deep breaths creates hypocapnia (low CO2), which delays the urge to breathe without meaningfully increasing oxygen. The result: divers can swim until oxygen drops to critical levels without warning, then lose consciousness suddenly.

This is the mechanism behind shallow water blackout—responsible for numerous deaths annually, even in shallow water. Proper freediving breathing involves calm, relaxed breaths, never hyperventilation.

Ascent Blackout

During ascent from depth, pressure drops cause oxygen partial pressure in your lungs to fall rapidly. Oxygen can actually diffuse from blood back into lungs—the reverse of normal respiration. The last 10 metres represent the greatest proportional pressure change, making this the danger zone where most blackouts occur.

Pressure Effects on the Body

Ambient pressure increases by one atmosphere for every 10 metres of descent, creating specific challenges for air-filled spaces in your body.

Ear Equalisation

The most immediately noticeable pressure effect is in your ears. Without equalisation, pressure differentials cause pain and can lead to barotrauma. Our equalization techniques guide covers the methods in detail.

The Valsalva manoeuvre (pinching nose and exhaling) works for shallow depths but has limitations. The preferred technique is the Frenzel manoeuvre, which uses the tongue as a piston and is far more efficient at depth.

Lung Squeeze

"Lung squeeze" occurs when blood shift cannot fully compensate for lung compression, causing fluid or blood to leak into alveoli. Risk factors include diving too deep too quickly, cold water, and insufficient warm-up. Prevention involves gradual depth progression over months or years.

Training Adaptations

Regular freediving practice produces documented changes throughout your body.

Enhanced Diving Response: Trained freedivers exhibit stronger bradycardia, more intense vasoconstriction, and more reliable spleen contraction.

CO2 Tolerance: Through repeated exposure, freedivers develop increased tolerance to elevated carbon dioxide.

Thoracic Flexibility: Greater chest and lung flexibility reduces demands on blood shift and lowers lung squeeze risk.

Hypoxia Tolerance: Trained freedivers can maintain consciousness at oxygen saturations that would render untrained individuals unconscious.

Safety Implications

Understanding freediving physiology is essential for safety. Most accidents stem from failures to respect physiological limits.

Never Dive Alone: The diving response that conserves oxygen so efficiently also means blackout can occur suddenly. A trained buddy is essential—see our buddy system guide.

Respect CO2: Your urge to breathe is a sophisticated warning system. Never hyperventilate or ignore extreme air hunger.

Progress Gradually: Adaptations develop over months and years. Attempting depths your body isn't prepared for invites injury.

Surface Intervals Matter: Adequate recovery time between dives is essential. Minimum two to three times dive duration for most recreational diving.

The physiology of freediving reveals something profound: we are not purely terrestrial creatures. When you freedive, you're expressing a capacity that has been part of human physiology since our aquatic heritage. Understanding this science allows you to work with your body, developing your diving ability safely and progressively.

This article is for educational purposes and does not constitute medical advice. Always seek proper training from certified instructors. If you're considering your first course, check out what to expect from your first freediving course.

Freediving Physiology — Complete Series

- 1Freediving Physiology: What Happens to Your Body Underwater

- 2The Mammalian Dive Reflex: Your Body's Ancient Diving System

- 3Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Freediving Training

- 4Blood Shift: How Your Body Protects Your Lungs at Depth

- 5Oxygen and CO₂: Understanding the Gases That Control Your Breath-Hold