Shallow Water Blackout: The Silent Killer in Freediving and Swimming

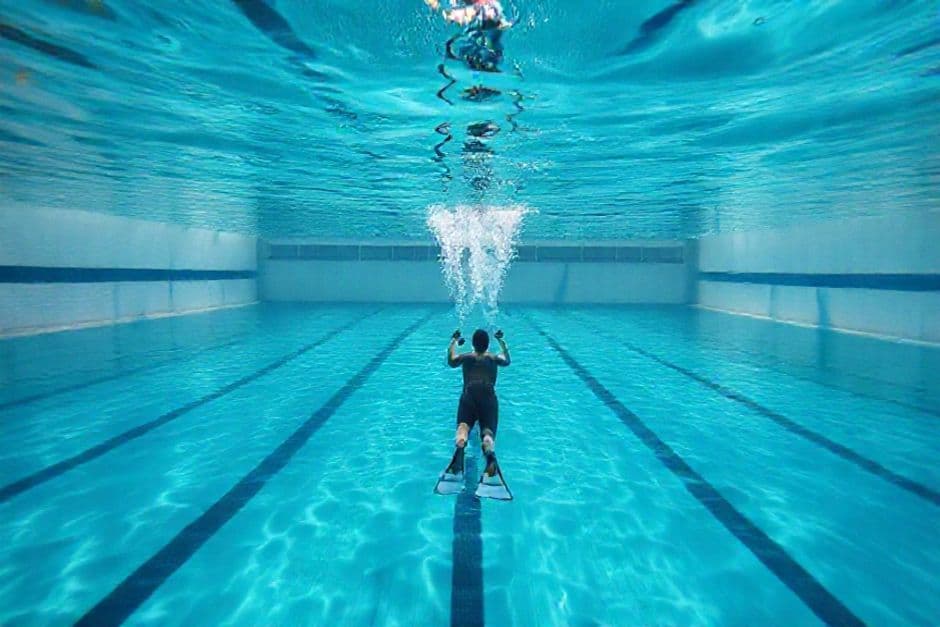

Shallow water blackout is a loss of consciousness caused by lack of oxygen to the brain, occurring without warning during or immediately after a breath-hold dive. It kills fit, experienced swimmers — often in pools, often while being watched — because victims show no signs of distress before losing consciousness. It's called "the silent killer" because there's no struggle, no splashing, no cry for help.

An estimated 20% of all drowning deaths may be attributed to shallow water blackout, and it's believed to be the leading cause of drowning among competent swimmers. This article explains what causes it, who's at risk, and how to prevent it.

What is Shallow Water Blackout?

Shallow water blackout (SWB) — also called hypoxic blackout or underwater hypoxic blackout — is the loss of consciousness underwater caused by oxygen deprivation to the brain (cerebral hypoxia). It typically occurs towards the end of a breath-hold dive when oxygen levels drop below the threshold needed to maintain consciousness.

The American Red Cross, YMCA, and USA Swimming define it as: "the loss of consciousness in the underwater swimmer or diver, during an apnea submersion preceded by hyperventilation, where alternative causes of unconsciousness have been excluded."

What makes SWB particularly dangerous:

No warning signs: Victims don't experience panic or urgent need to breathe before losing consciousness

Affects strong swimmers: The fitter you are and the longer you can hold your breath, the higher your risk

Happens in shallow water: Most incidents occur in swimming pools or water less than 5 metres deep

Quick progression: Brain damage begins within 2-3 minutes; death can follow rapidly

The Physiology: Why Your Body Fails You

Understanding why SWB happens requires understanding what makes you want to breathe.

The urge to breathe is driven by carbon dioxide (CO2), not lack of oxygen. As CO2 builds up in your blood during a breath-hold, it triggers increasing discomfort — the "air hunger" that eventually forces you to surface and breathe. This is your body's early warning system.

The problem: hyperventilation defeats this warning system.

When you hyperventilate (take multiple deep, rapid breaths) before a breath-hold, you "blow off" CO2 from your blood. This doesn't significantly increase your oxygen stores, but it dramatically reduces your CO2 levels. The result:

Your urge to breathe is delayed because CO2 takes longer to reach uncomfortable levels

You continue your breath-hold, feeling fine

Meanwhile, oxygen continues depleting

Oxygen drops below the threshold for consciousness (25-30 mmHg) before CO2 rises enough to trigger urgent air hunger

You black out — often just metres from the surface, often just seconds from safety

As one researcher put it: "The reason you black out is you've used up all your oxygen and you just didn't know it because you've blown off all your CO2."

Types of Freediving Blackout

Freediving blackouts are classified by when and where they occur:

Shallow Water Blackout (Isobaric)

Occurs in shallow water (typically less than 5 metres) where pressure changes are minimal. Most common in pools and during breath-hold swimming. The primary cause is hyperventilation before the dive, which suppresses the urge to breathe until oxygen is critically depleted.

Ascent Blackout (Deep Water Blackout)

Occurs during ascent from deeper dives, typically in the final 10 metres before the surface. As the diver ascends, decreasing water pressure causes gas in the lungs to expand (Boyle's Law). This rapidly drops the partial pressure of oxygen in the blood, sometimes causing oxygen to actually flow back from the blood into the lungs.

Ascent blackout is the most common form in competitive freediving. Victims often appear fine during the dive, then lose consciousness in the final 3-5 metres — sometimes breaking the surface before blacking out.

LMC / Samba

Loss of Motor Control (LMC), also called "samba," is a precursor state to full blackout. The freediver surfaces but experiences involuntary muscle contractions, loss of coordination, confusion, or inability to control their body. It looks like the diver is "dancing" — hence the nickname.

LMC is arguably more dangerous than blackout because the diver may attempt to breathe but cannot control their airway. Without immediate buddy assistance, LMC can progress to full blackout and drowning.

Who is at Risk?

Shallow water blackout most commonly affects:

Males under 40 — approximately 86% of victims are male

Fit, experienced swimmers — the ability to hold your breath longer increases your risk

Competitive swimmers — training motivation can override safety instincts

Spearfishers and freedivers — particularly those who dive alone

Intermediate freedivers — beginners lack the adaptation to push into dangerous territory; intermediates have enough skill to be dangerous

Counterintuitively, beginners are less at risk because their breath-hold capacity is limited. It's the intermediate diver — trained enough to hold their breath for extended periods but not trained enough to understand the risks — who is most vulnerable.

The Statistics: How Many People Die?

Shallow water blackout is significantly underreported because many deaths are classified simply as "drowning" without investigation into the mechanism.

Global estimates:

Approximately 140,000 drowning deaths occur worldwide each year

SWB is estimated to cause 20% of all drownings — potentially 28,000 deaths annually

Some experts estimate SWB causes over 50% of drownings among competent swimmers

Nearly all drownings of advanced or elite swimmers are believed to be SWB-related

DAN Research (2004-2017):

995 breath-hold incidents reported

73% were fatal

Average age of victims: 41 years

86% were male

Activities: snorkeling (46%), spearfishing (25%), freediving (18%), collecting (11%)

In the United States alone, approximately 4,000 drowning deaths occur each year. While overall drowning rates have decreased over decades, the rate of SWB deaths has not decreased — likely because awareness remains low.

Real Cases: When Strong Swimmers Die

These cases illustrate how SWB claims fit, experienced swimmers:

Tate Ramsden (2015)

A 21-year-old member of the Dartmouth College swim team, Ramsden died while swimming laps at a YMCA in Sarasota, Florida. He had already completed 4,000 yards when he attempted to swim four additional laps without taking a breath. Despite lifeguards being present, he had to be pulled from the pool after losing consciousness.

James Warnock

A three-time North Atlantic Spearfishing Champion, the 31-year-old drowned in a medical-therapy pool while practicing breath-holds for the National Spearfishing Championships. The water was chest-deep and warm. His family has since become advocates for SWB awareness.

Whitner Milner

Whitner was practicing breath-holding in his family pool when he succumbed to SWB. His family founded the Shallow Water Blackout Prevention organization (now Underwater Hypoxic Blackout Prevention) to raise awareness and prevent similar tragedies.

The common thread: all were competent to excellent swimmers, in controlled environments, often with others nearby. SWB doesn't discriminate by skill level — it targets those who push their limits.

The Hyperventilation Myth

Many swimmers believe hyperventilating before a breath-hold helps them hold their breath longer by "loading up on oxygen." This is dangerously wrong.

Hyperventilation does not significantly increase oxygen stores. Your blood is already 97-99% saturated with oxygen during normal breathing. What hyperventilation does do is:

Dramatically reduce CO2 levels in your blood

Delay or suppress the urge to breathe

Create a false sense of extended capacity

Allow oxygen to deplete to dangerous levels without warning

Any perceived "benefit" of hyperventilation comes from suppressing your body's warning system, not from improved oxygen capacity. You're not gaining time — you're losing your safety margin.

Why Lifeguards Miss It

SWB victims don't look like they're drowning. There's no:

Splashing or struggle

Calls for help

Panicked movements

Arms waving

Instead, videos of SWB show swimmers transition smoothly from active swimming to an unconscious float or glide. They may drift to the bottom or glide along until they stop. To an untrained observer, it can look like a normal pause in activity.

Signs to watch for:

Swimmer stops moving for no apparent reason

Body goes limp or begins to sink

Head falls forward

Large bubbles released from the mouth — "big bubbles mean big trouble"

Twitching or spasms (if LMC is occurring)

The critical rescue window for SWB is much shorter than typical drowning — resuscitation needs to begin within about 2 minutes, compared to 6-8 minutes for standard drowning, because the body is already severely oxygen-deprived.

Pool Dangers: Hypoxic Training Bans

The danger of SWB is now so well-recognized that major swimming organizations have banned or restricted hypoxic training:

USA Swimming — bans hypoxic training for competitive swimmers; advises restricted breathing only on the surface

American Red Cross — warns against breath-holding games and extended underwater swimming

YMCA — prohibits prolonged underwater breath-holding

Many UK pools — have prohibited hypoxic training during recreational sessions

Michael Phelps and his coach Bob Bowman recorded a public service announcement warning swimmers about SWB, emphasizing that even Olympic athletes are at risk.

Bottom line: There is no scientific evidence that underwater breath-hold training provides meaningful benefits that can't be achieved through surface-level restricted breathing exercises — and the risks are potentially fatal.

Prevention: How to Stay Safe

The Golden Rule: Never Dive Alone

Without a buddy, you will die if you experience shallow water blackout. This isn't exaggeration — it's physics. An unconscious person underwater cannot save themselves.

Proper buddy protocol:

"One up, one down" — when your buddy is underwater, you are at the surface watching. Never breath-hold at the same time.

Stay within arm's reach of your surfacing buddy

Watch for at least 30 seconds after surfacing before starting your dive

Your buddy should be able to swim down and retrieve you if needed

If practicing in a pool, have someone on deck watching who is not training

Never Hyperventilate

Before any breath-hold:

Take only 2-3 calm, relaxed diaphragmatic breaths

Do not take rapid, deep breaths

Focus on relaxation, not "oxygen loading"

If you feel lightheaded or tingly from breathing, you've hyperventilated — stop and wait

Know Your Limits

Never push to your absolute maximum

If you experience an LMC or blackout, you're done for the day — exit the water

After any blackout, wait at least 24 hours before diving again

Competitive drive and peer pressure cause deaths — know when to stop

Never Play Breath-Holding Games

Underwater breath-holding contests, "who can swim furthest" challenges, and similar games have killed children and adults. There is no safe way to compete at breath-holding without trained supervision and rescue capability.

What to Do if You Witness a Blackout

If you see someone lose consciousness underwater, remember the Four Rs:

1. Recognize

Watch for: stopped movement, sinking, limp body, head falling forward, large bubbles from mouth, twitching.

2. Retrieve

Get them to the surface immediately. Support their head above water with their airway clear. Speed is critical — brain damage begins within 2-3 minutes.

3. Revive

Use the "Tap-Blow-Talk" method:

Tap — tap their cheeks firmly

Blow — blow sharply on their face (triggers breathing reflex)

Talk — speak loudly: "Breathe! You're okay! Breathe!"

If they don't respond within 10-15 seconds, begin rescue breathing. Call emergency services.

4. Recover

Even if the person regains consciousness and seems fine, they need medical evaluation. Keep them out of the water for at least 24 hours. Multiple blackouts or LMCs indicate they need to reassess their training.

Summary

Shallow water blackout is the silent killer of the freediving and swimming world:

It kills without warning — victims feel fine until they lose consciousness

It targets strong swimmers — the better you are at holding your breath, the higher your risk

Hyperventilation is the trigger — it doesn't increase oxygen, it removes your warning system

An estimated 20% of all drownings may be SWB-related

Prevention is simple: never dive alone, never hyperventilate, never push to maximum

Every freediver, spearfisher, and competitive swimmer needs to understand SWB. The sport can be practiced safely — but only with proper knowledge, proper supervision, and proper respect for the physiology that can turn a routine breath-hold into a fatal event.

The number one rule in freediving: Never dive alone. Your buddy is your life insurance.

For more on freediving safety, see our guide to the buddy system, or learn about proper breathing techniques that keep you safe. Ready to start freediving the right way? Explore Melbourne training options.

Freediving Safety — Complete Series

- 1Is Freediving Dangerous? Risks, Statistics & How to Stay Safe

- 2Shallow Water Blackout: The Silent Killer in Freediving and Swimming

- 3Freediving Deaths: Causes, Prevention & What We Can Learn

- 4Freediving Safety: The Buddy System - Your Lifeline Underwater